Payam Zamani on Crossing the Desert

"I am going to die here, I thought. Then I spotted something."

Hey There Soul Rebels!

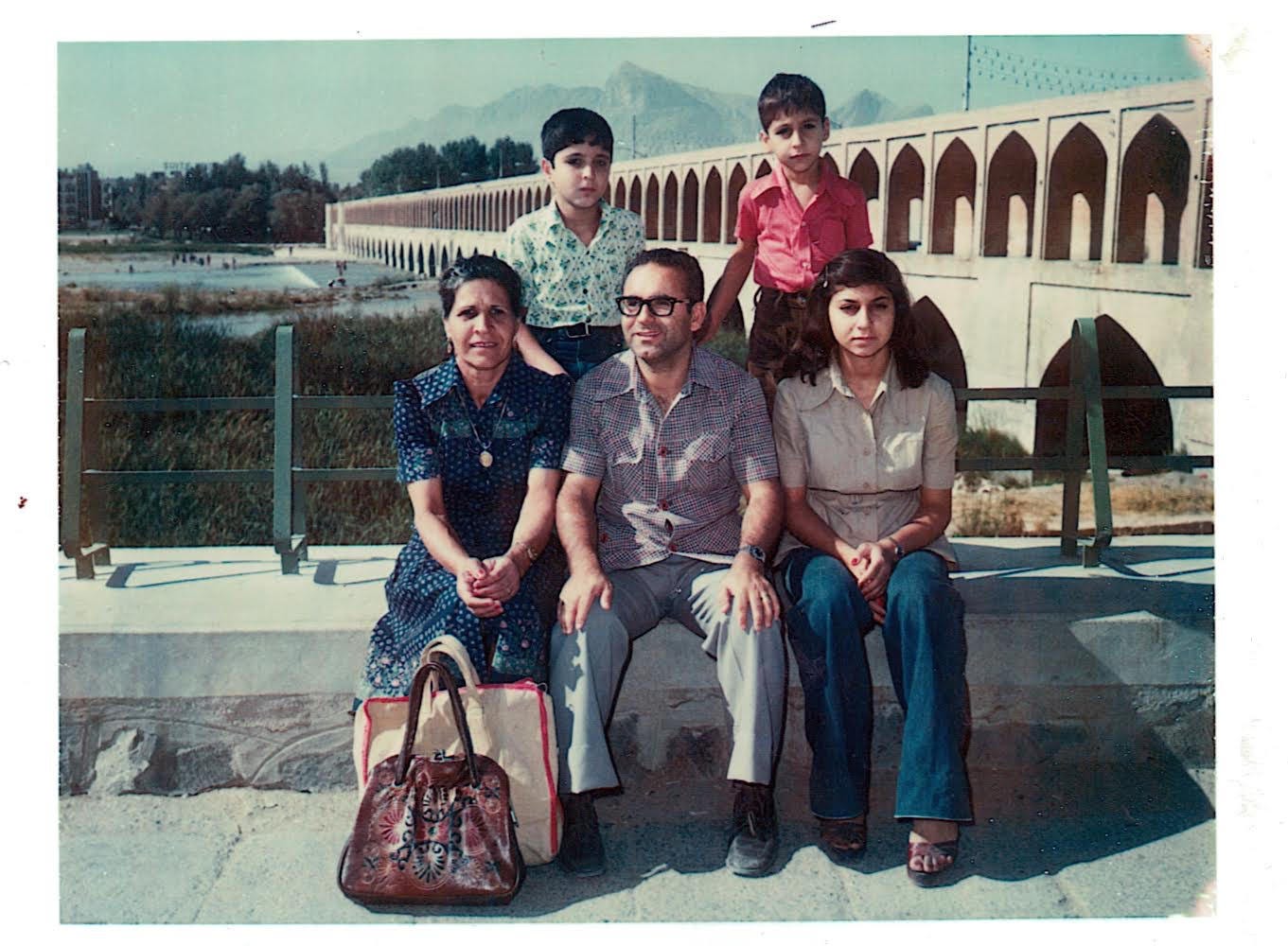

This week, I’m thrilled to have Payam Zamani on the Soul Boom podcast. Payam’s journey is nothing short of extraordinary. Born in Iran to a family persecuted for their peaceful Bahá'í beliefs, Payam endured numerous traumas before finding his way to the US as a refugee. His journey from fleeing Iran to launching a billion-dollar IPO on Wall Street is the epitome of the immigrant's American Dream.

But Payam’s story is not just about financial success. It's also about the deep losses he faced and his discovery of the vital role of faith and spirituality in our lives. Today, as the leader of One Planet Group, he models a business approach that integrates economic life with service and values.

Payam details all this and more in his new memoir, Crossing the Desert, a heart-pounding, warm-hearted story of resilience and hope.

For today’s edition of the Soul Boom Dispatch we’re sharing an excerpt. In this passage we join a teenage Payam, five other teens, and two smugglers, as they make their way to the Pakistan border in their attempt to escape from Iran. And, because this month marks the 41st anniversary of the execution of ten Bahá’í women in Shiraz, Iran, we wanted to share a new music video that honors them from nine-time Grammy nominated jazz singer Tierney Sutton and her virtuoso guitarist husband, Serge Merlaud.

Enjoy,

Rainn

THE GREAT ESCAPE

By Payam Zamani

We finally stopped at the edge of an embankment, and the smugglers let us sit up…

While we sat there, the smugglers told the girls that they had to get rid of most of their luggage to lighten the load for the upcoming portion of the trip. I wondered why they didn’t mention that back in Zahedan. Surely, they knew where they were taking us.

At first, the girls refused.

“Then we’ll have to leave you here in the desert for a day or two,” they told us all, “and we’ll come back with more help to carry everything.”

No one could survive in that desert for a day or two.

We all knew what they meant.

They would never come back. They would leave us to die.

The girls had no choice. They left most of their belongings behind, knowing that the smugglers would surely come back later and collect the precious things they had carried from home, either to take for themselves or to sell for more profit than they were already making from our desperate situation. Or maybe the things they were carrying were the very reason they were choosing to leave the country in this way in the first place, rather than leaving legally. I would never know.

As we sat near the road, the smugglers waited and watched. They familiarized themselves with the timing of the border patrol. Once they saw an opportunity, they said, “Hold on.” They put the truck in neutral and we silently rolled down the embankment and straight across the road.

That’s when the second smuggler jumped out and grabbed a broom that was lying beside me. I watched as he swept away the dirt tracks our truck had left on the asphalt. He jumped back in, the driver turned the key, and we sped off into the desert. We all stayed sitting up in the back of the truck at this point, and I didn’t see any headlights coming from the road behind us.

We’d made it without being spotted.

Everyone exhaled.

From there, the trackless, rocky terrain started to turn mountainous, and after thirty minutes, we reached a rough and narrow trail that the truck could no longer navigate.

As we climbed out, we saw six beat-up dirt bikes, each with a driver, waiting for us. The six of us got on separate bikes with one tiny bag each latched to the back, and we held on for our lives as we sped off through the hills. Without any headlights, we wove through rocky ravines, deep sand, and salty dry soil, dust filling our noses and mouths. The roar of the motorcycle engines echoed out into the empty desert, hopefully far enough away from anyone to be heard.

Finally, beat up and exhausted from all the pounding on our bodies, we stopped at a rugged, mountainous place where even the bikes could go no farther. There were two more people waiting for us there, in the middle of nowhere, at what must have been sometime after midnight.

“What’s happening?” the oldest girl asked.

“From here, we go on foot,” they said.

I looked up at the moonlit, steep, nearly sheer wall of the canyon in front of us and thought, This trip is about to get much harder than I ever imagined.

The smugglers told us the wall had been created by government bulldozers and dynamite to make it impossible for people to climb.

Clearly, they underestimated just how badly some people wanted to leave.

We had to claw our way on our hands and knees, with loose dirt and rocks tumbling down all around us as we dug in our fingernails and ascended.

We were all young and fit, and we eventually made it to the top, panting and gasping for breath, filthy, but with our hope alive. Squinting into the distance, I saw nothing but bare mountains, stone, and sudden sharp crags pointing up into the night sky. There wasn’t a plant or a tree growing anywhere.

“Is this the border?” one of the girls asked.

The smugglers just shook their heads and pointed forward, toward even higher peaks.

“Go,” they said. “We must go.”

The smugglers hurried us along, never allowing us to stop for rest and only occasionally offering us water from one small jug, which we all shared, from which they insisted we drink sparingly. We used no lights, not even a tiny flashlight, only navigating by the dim glow of the moon.

Somewhere along the narrow passageways, I asked one of the smugglers how much longer we had to go.

“About fifteen minutes,” he said in a thick Baluchi accent that I could barely understand.

Thirty minutes passed. I asked him again, “How much farther?” “Fifteen more minutes,” he said.

I kept asking, and we kept walking.

Five hours later, we emerged onto a vast, flat plateau. We were famished, dehydrated, completely drained, and covered in dirt. As the wind blew across the sand, we collapsed. We all just fell to the ground, on the hot desert floor. Two smugglers, two boys, and four girls, watching the sun rise in front of us, knowing that its heat would soon kill us if we weren’t rescued.

I asked one of the smugglers, “Why didn’t you tell us we would be hiking for five hours? Why wouldn’t you tell me the truth about how much farther we had to go?”

“I had to break the news to you in pieces,” he said. “Anyone can hike for fifteen minutes at a time, but if you knew the hike was going to be five hours, the weak would have given up and been left behind to die.”

I’m not sure I want to know the story of how he came up with that approach. But it worked.

As we sat there, resting, an hour went by, and the sun rose higher in the sky.

“Why are we just waiting here?” I asked. “Trucks will come,” he said.

“When?”

He didn’t answer.

I am going to die here, I thought.

Then I spotted something. Dust rising into the air. In the distance, two vehicles were speeding through the desert.

We all sat up. Soon, we could make out the details of two Toyota pickup trucks headed our way. It wasn’t until they were close enough to see through the windshields that I noticed that the steering wheels were located on the right-hand sides of the vehicles, rather than the left.

It was July 7, 1987, and I knew we’d made it to Pakistan.

The drivers pulled up and asked us to get in.

With hardly an ounce of strength left, I stood up, knowing that any one of the smugglers could easily kill me right there for the money I carried and the clothes in my bag, and there wouldn’t be anything I could do about it. I couldn’t fight. I couldn’t run. I had no defenses. I was an illegal immigrant in one of the most treacherous parts of the world, and I was completely at their mercy.

But I also knew I had escaped Iran.

And I prayed that mercy would be shown.

Reprinted with permission from “Crossing the Desert: The Power of Embracing Life’s Difficult Journeys” by Payam Zamani (BenBella Books, 2024). Payam Zamani is an entrepreneur, philanthropist and investor. He is the founder, chairman and CEO of One Planet Group, a hybrid tech firm that runs a suite of online technology and media businesses with a mission to improve our world.

Music Video: “Ten” by Tierney Sutton

The song “TEN” was written as part of the #OurStoryIsOne campaign marking the 40th anniversary of the execution of ten Baha’i women in Shiraz, Iran on June 18, 1983. These valiant women, ranging in age from 17 to 57, chose to give their lives rather than recant their faith.

June commemorates the 41st anniversary of their martyrdom and the second year of the awareness campaign. The animated music video narrates their legacy of sacrifice through a mythical fable:

The individuals responsible for their demise believed they could snuff out their light and bury their memory. Instead, from the seed of their sacrifice—like flowers rising from the darkest earth—their message and memory continues to blossom and bloom.

The #OurStoryIsOne campaign celebrates the resilience of Iranian women of all faiths and backgrounds in the face of oppression. As Tierney says: “The song is about the Shirazi Ten—but we also wanted to spotlight the continuing persecution of women around the world and say something about how the sacrifice of these ten women continues to inspire.”