Salutations, Generation Soul Boom!

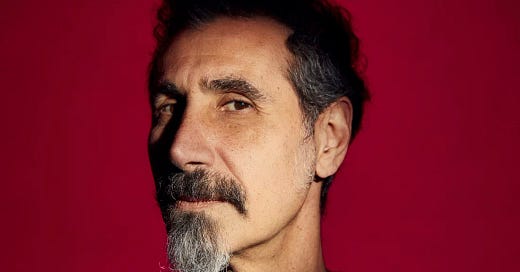

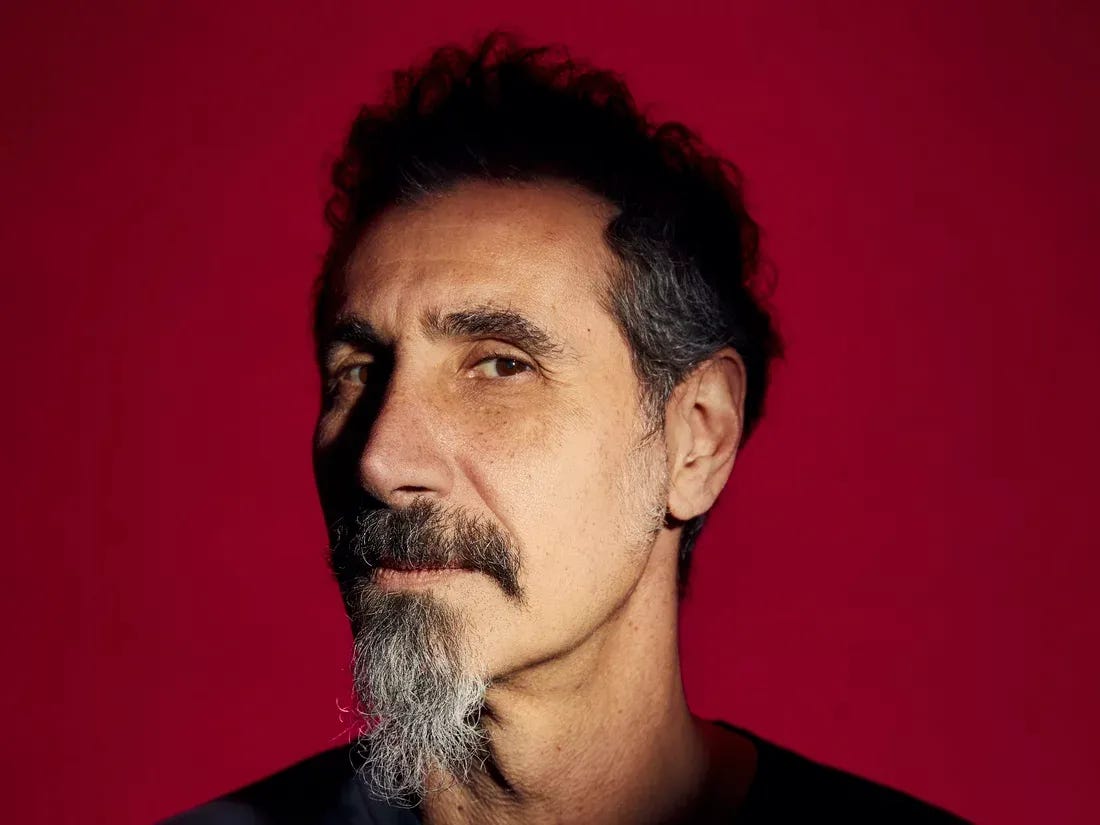

This week on the Soul Boom podcast, we’re bringing back one of our most popular episodes to date: Rainn’s conversation with the iconic Serj Tankian. It’s a heartfelt and deep exchange we think you’ll enjoy even if it's your second (or third) listen.

It’s particularly good timing, as just last week Serj dropped a music video from his new solo EP, now available everywhere via Gibson Records. And of course, in the aftermath of a momentous presidential election here in the US, we find clarity in Serj’s perspective. (But we digress…)

We stand in awe of Serj’s powerful voice, both sonically and artistically. Even if you're not the world’s biggest fan of his music, Serj’s journey contains a multitude of life lessons and deep experiences. So, this week we're sharing an excerpt from his book Down With the System: A Memoir (of Sorts). In it, Serj guides us through his unlikely trajectory from immigrant entrepreneur to nu metal poet laureate. As he confesses about System of a Down, “... we were as unlikely a chart-topper as had ever existed in modern music history: a band of Armenian-Americans playing a practically unclassifiable clash of wildly aggressive metal riffs, unconventional tempo-twisting rhythms, and Armenian folk melodies, with me alternately growling, screaming, and crooning lyrics that could pivot from avant-garde silliness to raging socio-political rants in the space of a single line. I’d be the first to admit it: it’s not easy listening.” But easy listening was never his goal. As Serj explains, he was an activist long before he was an artist and he “never wanted to be one of those vacant souls who speaks to millions but talks to no one.”

Yet as Serj found out, speaking your truth can provoke strong and sometimes negative reactions.

When SOAD’s second album Toxicity hit number one, that success was drowned out by the events of that day. It was September 11, 2001.

In the aftermath of the horrific attacks on 9/11, a huge wave of grief and anger swept across America. From Serj’s point of view, the current of the times went beyond mere patriotism and entered into a state of jingoistic nationalism. He found the understanding of the events and their underlying causes reductive and lacking in nuance. Hailing from a people and family that had experienced first hand the traumas of oppression and genocide (as well as the denial of that experience), Serj was convinced understanding history and root causes was key to making sense out of how we as a species got to this place…. And also key to finding a new and better path for all of us, collectively. So he decided to write and post an essay with his geo-political analysis, just two days after the attacks.

As Serj tells us, in spite of his best intentions, his essay, “... did not go over well. At all. The way a lot of people viewed it was like this: the whole nation is in shock and mourning, and the lead singer of one of the most popular bands in the country is suggesting that we might have brought this upon ourselves. That it’s our fault… I was condemned in newspapers, on music websites, and all over the radio, including by Howard Stern, who was arguably the country’s most popular and influential media personality in those days…”

To defuse the tension, Serj agreed to go on Howard Stern’s show… But that wasn’t an easy time for Serj. “People sometimes ask me how excited I was when Toxicity came out and hit number one, but all I remember is being unbelievably stressed out. The fact is I had just turned thirty-four and didn’t really have the emotional and spiritual tools to deal with that kind of anxiety back then. I’d recently started meditating, but in the early days of my spiritual practice, I mistook passivity for nonaggression. When Howard was coming for me, I knew how to defuse his hostility, but not how to answer it. I hadn’t learned the virtues of compassionate confrontation. This wasn’t something I could simply read about or take a class on. It would take years, much experience, and the near collapse of System Of A Down, for me to fully understand it. Even today, it’s an ongoing process.”

That process was catalyzed by Rick Rubin's introduction of Serj to the pioneering meditation teacher Nancy Cooke de Herrera, who had herself learned Transcendental Meditation in an ashram alongside the Beatles and Mia Farrow. In Serj’s telling, the meditation practice she taught him changed his life and connected him to the experience of our oneness.

That experience of oneness, he assures us, is available to everyone.

Now let’s hear from Serj himself about how that whole story began…

Take it away, Serj!

The Soul Boom Team

Excerpt from Down With the System

By Serj Tankian

Remember that parable about how you have your whole life to make your first album? There’s a darker second half to it: generally, you only have about six months to make your second one. Oh, and it’s supposed to be better than its predecessor. That was kind of the vibe as the band started meeting up in a rehearsal space in North Hollywood to start working on new music. Our debut had exceeded expectations, which wasn’t hard because there weren’t really many expectations at all. Now there were…

The stress and the drama in those sessions was hard to escape. We were spending so much time and energy on the music, and even though I was thrilled with what we were coming up with, the strain could be a lot to handle. Usually, whenever I got stressed out or overwhelmed, I’d take a hot shower to unwind some of that tension. I’d stand there, eyes closed, head bowed underneath the shower head, with the scalding hot water pounding on the back of my head and neck, as the steam rose up all around me. More often than not, that would be enough to turn off all the noise and center me. But things got so bad around this time that when I’d close my eyes in the shower, I’d immediately be gripped by an almost existential fear. I’d be consumed by this very specific nightmarish vision of a large man standing behind a towering panel of electronic instruments. My pulse would race, my breathing would get shallow, and I’d be close to passing out. It happened again and again.

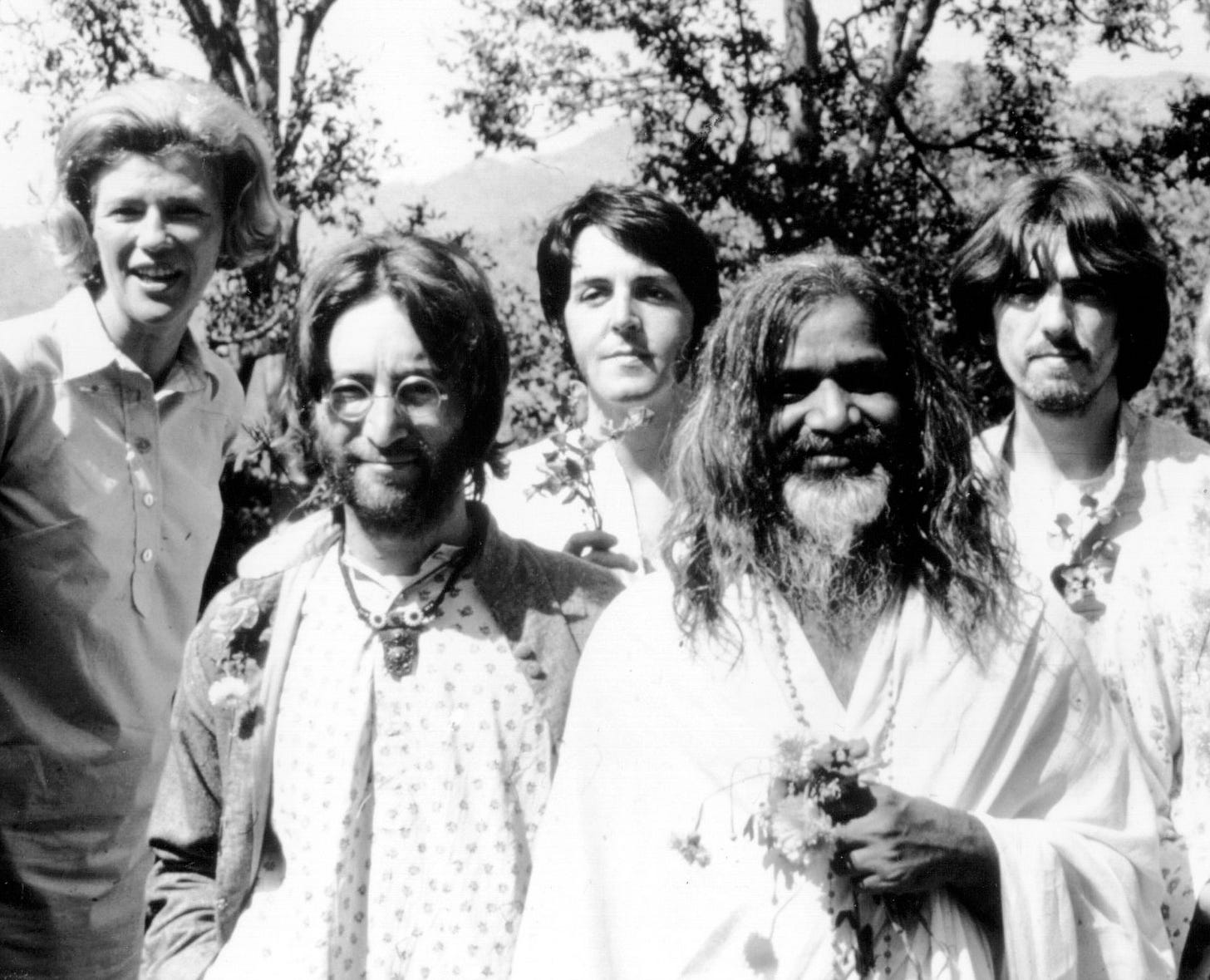

It wasn’t a huge stretch to see that vision as a distorted, fun-house mirror version of our recording process, or of my life, and to understand my reaction to it as a minor panic attack. Something like this had happened to me occasionally in the past, and in retrospect, it may well have been a case of the hot water in the shower lowering my blood pressure to a point where I was hallucinating and nearly losing consciousness. But it had never been this bad. I told Rick about what was happening, and he recommended that I go see a woman named Nancy de Herrera. Nancy had been an evangelist for transcendental meditation going back decades. In her younger years, she’d studied bacteriology at Stanford, then worked as something of an ambassador for the American fashion industry all over the world. She hung out with Jimmy Stewart, Esther Williams, and the shah of Iran. After the death of her second husband, a Formula 1 driver, a deep search for meaning had brought her to transcendental meditation. She visited India and Tibet dozens of times and became close with the Maharishi Mahesh Yogi. If you watch clips of the Beatles with the Maharishi in India in 1968, you can see Nancy, blonde and beatific, serving as a conduit between the Beatles and the guru.

Her proximity to the Maharishi put her in the orbit of a lot of interesting people. She rode camels on an expedition with Sir Edmund Hillary. She and the Dalai Lama chatted about yetis. In California, she’d become something of a TM teacher to the stars. Madonna, David Lynch, Lenny Kravitz, Rosie O’Donnell, and Sheryl Crow had all learned from her.

Of course, you’d know none of this by meeting her. She didn’t talk much about herself and didn’t come off as particularly showy. She was this sweet, older woman who looked very much like someone’s grandmother. When I arrived at her house, a beautifully manicured manor in Bel Air off Coldwater Canyon Avenue, we sat down and talked over tea and cookies.

I’d had some experience with meditation before. I’d read Jon Kabat-Zinn’s Wherever You Go, There You Are a year or two earlier and had tried meditating in dribs and drabs, but I’d never really committed myself to it before I started meeting with Nancy. The fact that she didn’t have the outer trappings of being some guru—there were no flowing robes, no turban, no trail of obsequious minions walking behind her—appealed to me. It was as if her very being was a reminder that meditation didn’t require superpowers. Anyone could do it.

Nancy gave me a mantra to focus on and taught me to repeat that mantra in my head, over and over, until it was all that remained. Everything else would begin to fall away. I’d just breathe in and out, in and out, and a calmness would descend. It was so simple yet unmistakably magical.

The goal was not so much to clear your mind as it was to slow it down. Nancy taught me that thoughts will always come when you meditate, and if you try to fight their arrival, they’ll only return with more insistence. So, the key is to watch the thoughts come but gently tell them that it’s not the right time to deal with them. Find a place in your mind where they can sit until later. She would even take phone calls during meditation sometimes. She’d tell me, “Don’t be so hard on yourself. If you have to pick up a call, pick up a call.” The goal was to make meditation a basic thing in your life, something accessible and easy to do every day, like walking.

Her home became such a tranquil place for me that I didn’t even need to meditate there all the time to gain some benefits. I can remember turning up there once while she was out walking her dogs, and before she even got back, simply being there, alone and quiet, had blissed me out. Just that pause in my day, in my week, in my life, had been enough.

Our lives tend to be such a hectic race of “Go! Go! Go!” that often what we need most is just to “Stop!” People are addicted to smoking cigarettes in part, I believe, because of the power and necessity of that spiritual pause. When people smoke, they’re getting in touch with their breathing. I’m not discounting the genuine addictiveness of nicotine, but in modern life, the physical act of smoking cigarettes is a ritual that often involves taking yourself out of a situation—work, dinner, whatever—standing outside and breathing in and out, over and over. That has value that stands apart from the sheer chemistry.

I found meditation incredibly emancipating, and the impacts for me were tangible. My meditation practice reminded me to listen more and react less. It also quickly brought on euphoric feelings of peace and made me think twice when I noticed judgmental thoughts creeping in. Essentially, the more I meditated, the easier it was for me to see the inherent good in people. Everyone is born pure, and it’s the very act of living—fighting for our survival—that beats the purity and goodness out of us. We’re all on the same journey together, different parts of a greater organism. So, if I’m out honking at some guy who just cut me off on the 405, that guy who just cut me off is also me. I’ve been there, I’ve done the same thing, so why heap my scorn on him? How is that serving either of us?

Meditation became a daily routine as important to me as eating and sleeping. It became so vital that I could really tell the difference if I hadn’t had time to meditate. I wouldn’t be as focused, as aware, as settled. It created this unique space for growth, change, and acceptance of whatever came my way. It gave me the tools to deal with the incredible metamorphosis that was going on in my life at the time. Every interaction was appreciated, every experience was accepted. I started to have more compassion toward others and their plight in what the author William Saroyan once termed this “human comedy.” I began to understand myself better, and why I had been the way I’d been for my whole life. I also began to appreciate the struggles of my band members better and their needs to be seen or heard or accepted. Being truly aware means taking in the full experience of someone else, knowing their history, empathizing with their story, and understanding why they make the decisions they do.

Meditation also opened my mind to new philosophies. I’d long been interested in indigenous cultures, and the more I learned about them, the more the idea of living in harmony with nature made sense to me. It felt not only important, but practical. I could see changes in my songwriting almost immediately. For the song “Aerials,” those lines, “Life is a waterfall, we’re one in the river and one again after the fall / Swimming through the void we hear the word, we lose ourselves, but we find it all,” are not something I would’ve conceived of before I’d started transcendental meditation.

My budding awareness from meditation enhanced and widened my activism, too. I became more sensitive to the inequities and injustices in our world, whether it was human rights abuses, invasions, wars, or environmental issues. It cleared the fog, in a way. I saw the injustice and was also able to understand the perpetrators of that injustice at the same time. From spiritual books, I segued into books about our combined indigenous past and its intuitive understanding of our journey on this planet. Stories about Native Americans, Aboriginal Australians, Māori, and indigenous communities from the Middle East shared similar customs, beliefs, and an underlying conviction about the importance of living within nature.

Inevitably, my outlook on life itself began to change as all of these new ideas took root. “Civilization is Over!” became my eco-political axiom. For ten thousand years starting with the agricultural revolution, humans evolved from hunter-gatherers to farmers, placing huge amounts of species into extinction over food competition. And yet, there’s a glaring irony here: even though we grow more food than we need, we haven’t been able to rid the world of hunger because the distribution of this food is based on privilege. The accelerated rate of destruction of natural resources on this planet coupled with the accelerated rate of overpopulation has been creating an inverse graph, making our current lifestyle increasingly unsustainable. Add to that the climate crisis and the human-footprint-based carbon warming and we have a real existential issue on our hands. So, the real question is what’s next? Is there a way out? To me, our only path forward is to match the intuitive understanding from our indigenous past with our modern intellect, technology, and logic. It’s the marriage of male and female energies. Without this cosmic marriage, we are doomed.

My spiritual awakening shifted the way I thought about our music, too. I’d recently learned about Buddhist sand mandalas, these intricate and beautiful pieces of art constructed by monks with colored sand. The most amazing part about them was that once they were finished, they’d quickly be destroyed or allowed to wash into the sea, vanishing without a trace. The destruction itself is in fact part of the artwork, a symbol that our time here on Earth is temporary, and its transience is what makes it so beautiful. It’s the process of making the art, the process of living itself, from which meaning, truth, and beauty are derived, not the product of that process. The product—whether it was a sandcastle, a painting, or an album—only offers an illusion of permanence. These too will eventually decompose and disappear, albeit on a different timeline. The art is always in the doing, not the memorializing.

I had to become okay with that impermanence, that my songs, my art, would one day fade into the ether from which they came. Doing so allowed me to ease my grip on the music, to begin to unravel my ego from the work. As artists, our job isn’t so much to create as it was to be open to the act of creation. The art is out there already; we just need to make sure we’re tuned in so that we can receive it and then present it skillfully.

It’s easy to get very New Age–y about all this, but meditation is a genuinely powerful tool. Our forebears understood this. A section of the Dead Sea Scrolls describes a nonreligious, nondenominational form of prayer—meditation, essentially—that was practiced thousands of years ago, which gave humans the power to materialize the reality they envisioned. This isn’t magic exactly, but the more you learn about it, the more it can seem like it.

And it’s not just the ancient sages who recognized this. It’s doctors and scientists, too. In 1981, a physician from Harvard Medical School traveled to the Himalayas to study Buddhist monks who practiced a meditation technique called g-tummo. These monks had been living at high altitude, in small, unheated huts for more than a decade. The doctor attached thermometers to the monks’ bodies and was able to document their ability to raise their body temperature by as much as seventeen degrees Fahrenheit after just a few minutes of using this meditation technique. Later studies documented similar feats, with monks able to dry wet sheets with only their body heat, raise the temperature of the room, or sit out in the mountains on subzero nights wearing nothing but a thin, cotton shawl. It’s literally mind over matter.

To be clear, I don’t heat my home with the power of meditation or go camping in the mountains without a warm coat and a cozy lodge at my disposal, but what meditation and my spiritual practice does for me is in many ways even more profound. I came to meditation looking for a way to relieve stress, to slow my mind from always running a hundred miles an hour, to help me learn to manage interpersonal relationships inside and outside the band. On a certain level, it helped to do all that for me quite quickly after adopting it.

Meditation is really the search for a feeling. If you’ve ever had a moment—maybe you’ve got headphones on, you’re listening to music, you’re staring out the window, or maybe your eyes are closed but you’re not asleep—and for just that moment there is nothing but that moment. There are no bills you’re worried about paying, there are no fraught conversations you’re replaying in your mind, there are no concerns of what came before or what comes next; that’s the feeling I’m aiming to conjure when I meditate. I’ve always thought of it as a portal to the most comfortable room in the house, the one I’m trying to get my being into. There are larger, more holistic goals, too, of course: to learn to exist in that moment all the time, to live a fully integrated life, to be a force for good in the lives of others, both those I know and those I don’t. I recognize these are goals I’ll never fully realize, but the very act of constantly striving and reaching for them is the whole point.

I’ve always felt that on the day of reckoning, if there is one, we will not be divided into believers and nonbelievers, but instead we’ll be divided between those who truly feel at one with all beings and the universe, and those who don’t. The greatest act of love is the opening of a door to a complete stranger. Acts of kindness are inspirational and often create a ripple multiplier effect that render a high quotient of positive productivity.

My meditation practice has evolved over time. Nancy first introduced me to TM, but since that time, I’ve learned more about it, adding and subtracting frequently to create a regular routine that works for me and changes as I change. Over the years, I’ve incorporated body meditation, Native American sun salutations, and even a vocal meditation for before I sing. I’ve created my own gratitude mantra—it’s really almost a poem—that I recite whenever I meditate now.

I admit I’ve become a bit of a spiritual dabbler, as my practice borrows elements from Buddhism, Sufism, and various indigenous cultures. I’ve absorbed the writings of Vietnamese monk and peace activist Thích Nhất Hạnh; Indian musician, poet, and philosopher Inayat Khan; and Tom Brown Jr., a naturalist and survival instructor from New Jersey. For me, the point is not to become someone’s acolyte, but rather to recognize that wisdom can come from many disparate sources. When you study meditation, you’re not only studying how to meditate more effectively, you’re studying how to live more effectively.

That said, spirituality does not exist in a vacuum. I can read books about it, I can talk to others who have wisdom and understanding, but real growth cannot be only theoretical. It’s lived experience that becomes your spiritual North Star. In other words, you often need to do things wrong to learn how to do them right.

Excerpt from Down With the System: A Memoir (of Sorts) by Serj Tankian. Serj Tankian is a musician, composer, activist, painter, entrepreneur, and poet—but you are probably most familiar with him as the lead singer of System of a Down, the beloved genre-bending band known for its powerful blend of aggressive metal, Armenian folk influences, and thought-provoking socio-political lyrics. In Down with the System, Tankian delves into his journey as an artist and activist, exploring the intersection of creative expression, spirituality, and cultural identity. Through his music, writings, and advocacy, Tankian champions a message of consciousness and compassion, inspiring audiences to look beyond convention and seek deeper connections to themselves and the world around them. Find him on social media: @serjtankian.