Sebastian Junger on Our Relationship with Death

“Dying is the most ordinary thing you will ever do but also the most radical.”

Dear Dispatchers,

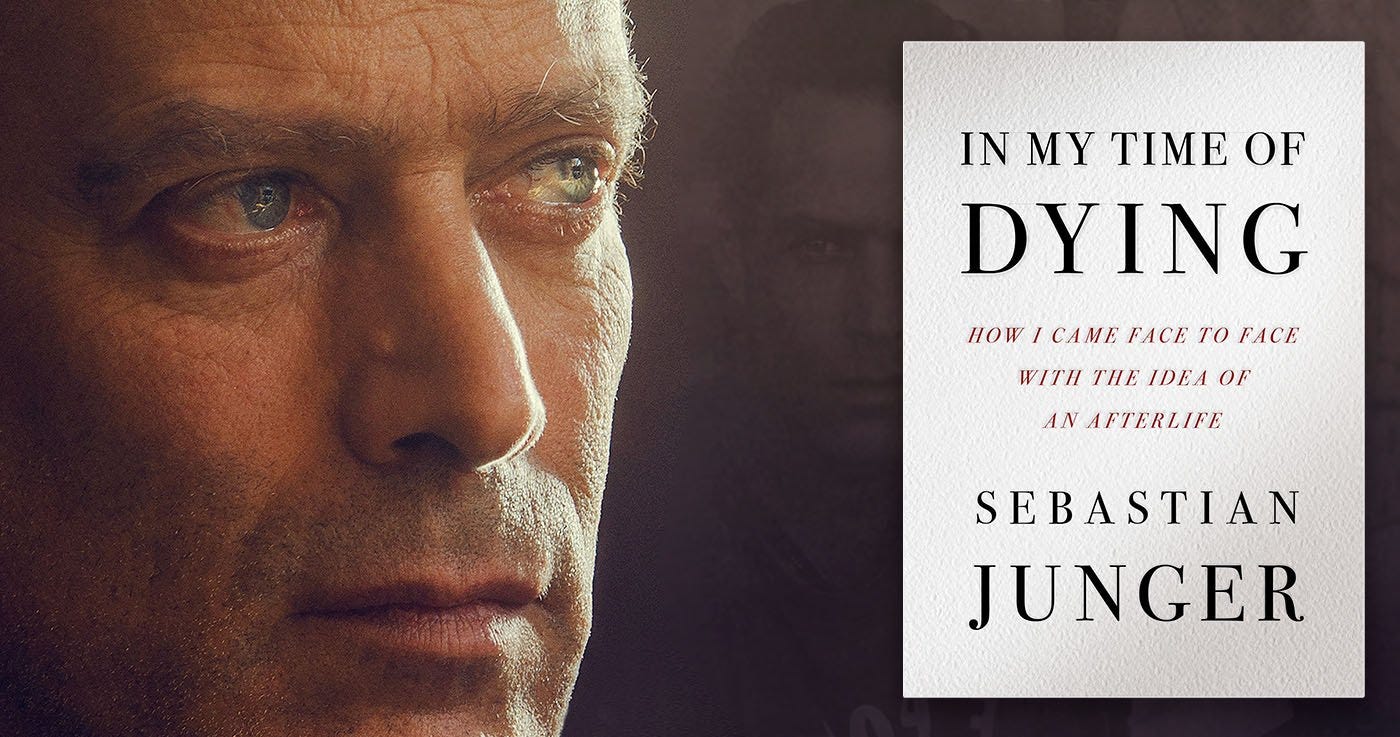

This week, we’ve got a treat for you on the Soul Boom podcast: Rainn sits down with Sebastian Junger, the brilliant journalist, Oscar-nominated filmmaker, and author whose latest book, In My Time of Dying: How I Came Face to Face with the Idea of an Afterlife, is nothing short of a deep dive into the big questions. And by “big,” we mean big—like life, death, meaning, randomness, and the possibility of an afterlife.

In June 2020, Junger had a brush with death that most of us only imagine in our darkest nightmares. A ruptured pancreatic artery aneurysm nearly claimed his life. While he was clinging to this life, he had a vision of his deceased father comforting him—a moment so profound that it launched him into an exploration of mortality and what might lie beyond—an exploration he embarks on with the scientific rigor his physicist father embodied. This isn’t your run-of-the-mill memoir; it’s a meditative, gut-punching, and ultimately life-affirming look at how we confront the ultimate unknown.

To give you a taste, we’re sharing an excerpt from In My Time of Dying that hits at the heart of it all: our uneasy relationship with death. Whether we obsess over it, try to outsmart it, or avoid thinking about it altogether, death shapes how we live in ways we often don’t realize. Junger, with his trademark blend of vivid storytelling and philosophical grit, examines the fragility of life, the randomness that defines our survival, and the powerful role love plays in grounding us amidst the chaos.

As we read, a few cosmic questions bubbled up: How do our brushes with mortality push us to find deeper meaning in our lives? How does the randomness of existence—the meteorite that misses by inches or the bullets that barely graze—remind us of life’s fragility and preciousness? And finally, how can love, as Junger’s young daughter so perfectly puts it—“stay here”—anchor us in the wild, unpredictable storm of life?

We hope this excerpt sparks some big reflections of your own. And don’t forget to tune into Rainn and Sebastian’s conversation on the podcast—it’s a deep one.

With love,

The Soul Boom Team

A Relationship With Death

From In My Time of Dying: How I Came Face to Face with the Idea of an Afterlife

by Sebastian Junger

Everyone has a relationship with death whether they want one or not; refusing to think about death is its own kind of relationship. When we hear about another person’s death, we are hearing a version of our own death as well, and the pity we feel is rooted in the hope that that kind of thing—the car accident, the drowning, the cancer—could never happen to us. It’s an enormously helpful illusion. Some people take the illusion even further by deliberately taking risks, as if beating the odds over and over gives them a kind of agency. It doesn’t, but it’s an odd quirk of neurology that when we are fighting the hardest to stay alive, we are hardly thinking about death at all. We’re too busy.

Dying is the most ordinary thing you will ever do but also the most radical. You will go from a living, conscious being to dust. Nothing in your life can possibly prepare you for such a transition. Like birth, dying has its own timetable and cannot be thwarted and so requires neither courage nor willingness, though both help enormously. Death annihilates us so completely that we might as well have not lived, but without death, the life we did live would be meaningless because it would never end. One of the core goals of life is survival; the other is meaning. In some ways, they are antithetical. Situations that have intense consequences are exceedingly meaningful—childbirth, combat, natural disasters—and safer situations are usually not. A round of golf is pleasant (or not) but has very little meaning because almost nothing is at stake. In that context, adrenaline junkies are actually “meaning junkies,” and danger seekers are actually “consequence seekers.” Because death is the ultimate consequence, it’s the ultimate reality that gives us meaning.

At 11:35 p.m. on October 3, 2021, a sixty-six-year-old woman named Ruth Hamilton of Golden, British Columbia, was woken up by a loud bang: a meteorite the size of a “large man’s fist” had crashed through her roof and come to a stop on the floral-print pillow next to her head. The meteor had been streaking through space for millions or billions of years. Its trajectory was non-random and mathematically predictable if you could know all the variables, which you couldn’t. Unlike tree work, they’re almost infinite. Hamilton’s survival came down to where she happened to lay her head. She spent the rest of the night sipping tea in an armchair and staring at the rock in her bed.

Combat reproduces that randomness extremely well. One day, I was leaning against some sandbags at a small American outpost in Afghanistan, and I felt some sand flick into the side of my face. Bullets travel roughly twice the speed of sound, so they arrive at their target well before the gunshots that fired them. The outpost was usually attacked from over a quarter mile away, which takes sound waves more than a second to cover. After the sand hit my face, I just had time to think What the hell was that? before hearing the rattle and clatter of distant machine gun fire. I was almost hit by the first rounds of the first burst of an hour-long attack. Like Ruth Hamilton in British Columbia, a few inches closer and I would never have known anything.

A few days later, we came under fire while on a foot patrol. It was plunging fire from across the valley that was almost impossible to take cover from; I found myself trying to hide behind a mountain holly hardly thicker than my arm. Bits of leaves drifted down from bullets that were chopping through the foliage over our heads, and gouts of dust erupted around my feet: more randomness. I was in and out of combat for a year, and the randomness never stopped—I just couldn’t let myself think about it.

Several years later, my friend and colleague from the Afghanistan deployment, British photographer Tim Hetherington, went off to cover the civil war in Libya. At the last moment, I had to pull out of the assignment, so Tim took a clandestine boat trip to the besieged city of Misrata on his own. He arrived in the morning and was in a firefight by noon. Two doomed enemy soldiers were trapped in a burning building dropping their last hand grenades down the stairwell. Tim went back to a journalist safe house a few miles from the front line and returned later in the afternoon, almost immediately getting hit by a single 81mm mortar from Gaddafi’s troops. One fighter lost his legs. A British photographer staggered away holding his abdomen to keep his intestines in. An American photographer named Chris Hondros took a chunk of shrapnel through the back of his head that did not kill him instantly but rendered him brain dead and beyond hope. And Tim took a small piece of metal to his groin—small, but apparently big enough to sever an artery.

The dead and wounded were loaded into a pickup truck, and the driver raced for the Misrata hospital. Tim bled out in the back of the truck looking up at the blue Mediterranean sky. The last thing he said was “Please help me” to a Spanish journalist who was sitting next to him. Did Tim know he was dying? Was he scared? He had no pulse by the time they got him to the hospital. Nurses rushed him into the trauma bay and gave him chest compressions, but there was no bringing him back. Because of Tim’s role documenting the war in Afghanistan, the US military made it clear that they would get his body out of Libya no matter what. Tim was buried in London on a fine spring day. The service was at the Church of the Immaculate Conception in Mayfair, and his closed casket rested on an ornate catafalque beneath the priest’s dais. One by one, Tim’s loved ones shuffled forward to pay their respects.

A few weeks after getting home from London, I found myself inhabiting a very different world from the one I’d left—dull, monochromatic, without much optimism or love. Against all logic I convinced myself that Tim’s death was my fault and that it should have been me and not him. Some days, I even caught myself thinking that he was the lucky one to have died; I was going to have to see my life through to the very end. Things unraveled quickly after that. My first marriage ended. My father died. The best man at my wedding rented a car, drove to a sporting goods store, bought a shotgun, and ended his life in a parking lot.

But the randomness that can kill you will also save you. One night I was in a crowded New York bar and glimpsed a woman who seemed inexplicably familiar. That was impossible—we’d never met—but I was overcome by the feeling I knew her. Later, she told me that she had experienced the same thing. We peered at each other in puzzlement and soon started talking. Her name was Barbara, she was a playwright and had a light Irish accent that came and went with the topic. Her father was fifty-three when she was born and had fought the entirety of World War Two on foot in Europe. He returned to become the mayor of his hometown and raise a family of twelve, of whom Barbara was the youngest.

We talked with a kind of shocked relief, as if we’d lost touch long ago and had finally run across each other again. Eventually we got married and had a little girl and then another little girl. We lived on the Lower East Side of Manhattan and in an old house in the woods in Massachusetts. One day when my youngest daughter was two, I told her that I loved her and asked if she knew what the word meant. “Yes, Daddy,” she said. “Love means, stay here.”

Excerpt from IN MY TIME OF DYING by Sebastian Junger. Copyright © 2024 by Sebastian Junger. Reprinted by permission of Simon & Schuster, NY.

Sebastian Junger is a celebrated journalist, bestselling author, and documentary filmmaker whose work delves into the profound intersections of survival, human connection, and meaning. Known for his books The Perfect Storm and Tribe, as well as the Academy Award-nominated documentary Restrepo, Junger’s storytelling has captivated audiences worldwide with its depth, honesty, and humanity. His latest work, In My Time of Dying, emerges from a life-altering health crisis and takes readers on a deeply personal exploration of mortality, near-death experiences, and the possibility of an afterlife. Through his characteristic blend of vivid narrative and philosophical inquiry, Junger continues to challenge and inspire readers to confront life’s greatest unknowns.

Thank you for an interesting conversation. I loved it. The line that struck me was when Sebastian said life doesn’t come into focus until death comes into focus which I found so profound. I think you could have a spinoff of a discussion on western culture and eastern culture on death which would be fascinating. I agree with Rainn that we in the western hemisphere are so disconnected with real death as opposed to what we see on tv/movies and in games. I don’t eat beef or pork for that reason you mentioned because I’m unwilling to watch the dying process of a cow or a pig going to slaughter. I watched several very close beloved family members die and it was excruciating and beautiful at the same time and feel very fortunate to be there when they passed through. Those experiences brought more focus and intentionality to my life and I’m so grateful for it.

Initially, my interest was to learn about Sebastian Junger's experience of the afterlife, despite the fact that I had other things I should have been doing. I continued watching because of the intelligent, and occasionally humorous, discussion between you both on the broader subjects of religion, interpretation of words, and animals other than human. The only thing that surprised me was when both of you talked about grieving for the loss of a pet in a non emotional, pragmatic way. Neither one of you mentioned that the animal shows such loyalty and affection without condition, which we seldom receive such a level of adoring attention from humans, therefore making sense that we grieve a pet, irregardless of the fact that we know approximately how long they may live. I will look forward to watching more of your podcasts. Thank you Rainn.