Hey There! Before we dive into Questlove’s theta brain waves, breathing rituals, and cosmic spark of creativity—just a quick word from our sponsor:

Yep. It’s Bragg’s Apple Cider Vinegar time. Again. And no, it still doesn’t taste like a dare.

Bragg’s new Organic ACV Blends keep all the gut-loving goodness of apple cider vinegar and mixes it with delicious ingredients. Think wellness potion, not witch’s brew. (Honey Cayenne? Citrus Ginger? It’s giving “elixir from a woodland apothecary,” not “bitter regret.”)

Same benefits, but with delicious flavor. It’s daily wellness that doesn’t feel like punishment.

They’re also giving a little Soul Boom boost: 20% off your first order of ACV Blends with code SOULBOOM at checkout.

✨ Go to www.bragg.com and grab yourself a bottle of the good stuff ✨

Okay. Back to Questlove and the spark that dwells inside us all.

Dear Soul Questers,

This week on the podcast Rainn sits down with Ahmir Khalib Thompson—better known as Questlove—the legendary 6-time Grammy-winning musician, drummer, record producer, DJ, Oscar-winning filmmaker, author, and culinary entrepreneur, to talk about—well—everything.

Creativity. Trauma. Mirror affirmations. The Emmett Till generation. Earth, Wind & Fire. Boredom. Orgasm length. The Theta brain state. And how the pandemic cracked something open in him that’s never quite closed back up.

It’s funny. It’s wise. It’s raw. And at the heart of it is a deeply personal awakening that began for Questlove in 2020, when the world stopped—and he finally, finally got quiet enough to meet himself.

During their conversation, Rainn describes creativity as a kind of Big Bang. A cosmic flicker that becomes color and chaos and galaxies. Questlove lives in that space. So this week, we’re also sharing an excerpt from his book Creative Quest, from a chapter aptly entitled “The Spark.”

We chose this passage because it has an egalitarian heart—very Soul Boom-y, if you ask us. In it, Questlove insists that creativity isn’t the property of elite artists. It belongs to anyone making something meaningful. He even sees creative work as a form of activism: a way to fight isolation, connect with others, and maybe even help heal the world.

We think you’ll dig it. And maybe it’ll convince you to grab the book too—it’s one of Rainn’s favorites (or so he keeps telling us).

Wishing you courage, clarity, and a deep breath on your own creative quest.

—The Soul Boom Team

The Spark

(Excerpted from Creative Quest)

By Questlove

It Is What It Isn’t

In the fall of 2016, just as I started working on this book, I participated in a keynote conversation with Malcolm Gladwell at a conference in New York City. It wasn’t a long conversation, and we didn’t have much time to talk onstage, but before the event, in the greenroom, I asked him one of my favorite questions. “Do you ever run out of ideas?” I said. He looked stunned for a moment. “What do you mean?” he said. “You know,” I said. “For books.” His answer was thoughtful. He talked about how some of his ideas don’t rise to the level of a book, and he has to rethink them later on, and how some of his ideas turn out to be parts of later, larger ideas. I heard it. But mostly I heard this:

No. No, I do not run out of ideas. There are secondary processes that matter much more, like refining an idea, perfecting execution, connecting an idea with the right audience, accepting critical assessment of it. But run out? No chance of that.

That conversation with Malcolm also reminded me of the stress points in any creative system. Again: creative people are always having ideas. That’s not the trick. The trick is learning how to capture them without being captured by them, how to display them without exposing too much of yourself, how to move forward while remaining unafraid to also move sideways or backwards.

Many books about creativity talk mainly about the journey. That’s fine. I like the idea of a journey, and I don’t even mind Journey that much—“Who’s Crying Now” is pretty undeniable. But I also work and have worked in the commercial arts, and that means that the journey has an eventual destination in the market.

This book is, in that sense, different from other books about creativity. I am assuming that what you do will end up somewhere, in front of the eyes or ears of others. It doesn’t have to be a traditional record store. But it has to end up somewhere.

Other books I have looked at say that the creative artist should start with no expectations, that he or she should practice automatic writing or let the mind drift into any corner of any idea. That may work well for a little while, but I’m against the broader implications of that theory. It’s not disciplined or directed enough. Everyone needs goals...

One of the most important strategies is negative affirmation. My late manager Rich used to talk about Maimonides’s concept of “negative theology,” where you know God only by what you can say that God is not. At the time it went over my head, but now that I’m older it makes a little more sense (plus, since he passed away I’ve gone back through all of his e-mails looking for moments of wisdom I might have missed). Give ideas that same respect. Carve out the negative space around your idea. If you know you are about to paint a portrait, make a list of all the things you don’t want it to be: overly realistic, say, or brightly colored. It’s sometimes hard to see the heart of an idea, so chip away at all the things that aren’t the heart.

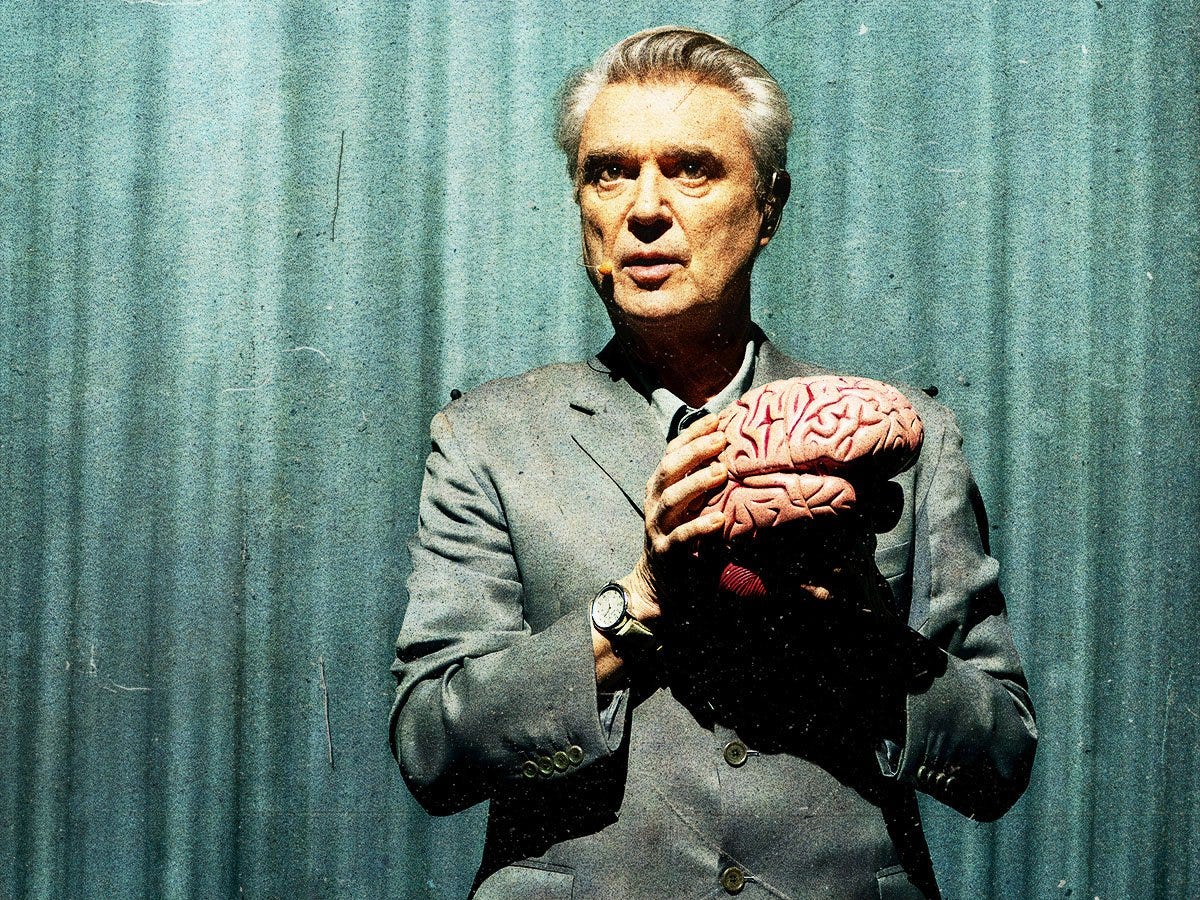

This also helps to focus your overall artistic goals. Back in 2013, I did a joint interview with David Byrne at NYU’s Skirball Center, and we talked about all different levels of creation. In our conversation, he echoed this idea: Don’t imagine what you will become—imagine what you won’t become. It helps to reinforce which parts of your creative identity you can’t live without, and which might be there only because you’ve been told by someone else that they should be there. Imagining what you won’t become is a necessary refining process.

It’s also something I think about all the time these days. One of the things that concerns me is the way my own creative work has proliferated. Not only do I colead the Roots (along with Tariq Trotter) and work on The Tonight Show, but I’m producing records, teaching college classes, DJing, writing books, and designing objects, and I have my own radio show and station on Pandora. I don’t say this to brag or even to #humblebrag. Far from it: I say it because I’m a little worried that all these responsibilities are working against the refinement that David Byrne was recommending. There are times now when I think I don’t really have a creative goal, other than the goal of continuing to do all these projects. Even though I have sixteen different jobs, it can sometimes feel like I don’t have any job at all.

When I remember David Byrne’s advice, that puts me back in mind of defining myself, if only for a second. What’s interesting about that process, when I engage in it, is how humbling it can be, because it separates work (jobs, responsibilities, obligations) from artistic identity (who I really am when I strip everything down to its essence). And the truth is that the things I do, the things I really am as an artist, are relatively specific things—things that, by the way, don’t fit into the overall matrix of contemporary popular art. No one is ever going to give out an award for Breakbeat Drummer of the Year, or Best Feng Shui Melodic Rhythm DJ Who Bases Much of What He Does on Soul Music and Hip-Hop but Also Incorporates Any Other Genre That Springs to Mind. The reason I know I possess a pretty specific, arcane skill is because I so rarely feel that it’s fully understood. The other day, I was at a party, first as a DJ, then as a guest, and toward the end of the night I ran into a music producer I know and respect. He came up to me and started talking about my DJ set, and how amazed he was at the way I let songs speak to each other and the way I built the whole thing as a work of architecture. I was amazed in return, because it reminded me of how rarely I hear a full account of what I do from someone who is both paying attention and who knows enough to reflect it back to me. That moment was very validating, and it helped me to get right back into that David Byrne question: What are you as an artist, and what aren’t you?

When I was talking to that music producer, when I was protected by a sympathetic audience of one, I could admit to myself that I wasn’t exactly a pop songwriter, or an instrumental virtuoso, or a legendary TV star, or a brilliant professor. And once I cleared all of that out, the essence of what I was doing—breakbeat drumming, feng shui melodic DJing—became something I could wear proudly, rather than something I felt apologetic about. Deciding what you’re not before you decide what you are lets you stand strong in your own category.

Making Things in the World and Remaking the World

When you make things, no matter what they are, no matter how generally you feel the impulse or how specifically you understand it, it immediately moves you into a different part of the human experience. It’s not necessarily better or worse—though I think it’s better in some way, obviously—but it’s different. Your brain and your soul are different after you’ve made something. So where does it leave you? What does it give you? At a fundamental level, what does it put into your bloodstream and your brainstream?

Laurie Anderson came to one of my food salons. It was a huge honor to have her there. At the time, she had just released Heart of a Dog, a mostly spoken-word album about death—the death of her dog Lolabelle, but also the deaths of her mother, Mary Louise, and of her longtime companion, Lou Reed. The album was strange and moving and sharp and all the things that people have come to expect from her. I was a little intimidated to talk to her, partly because of that, and partly because of “O Superman.” There aren’t many new wave or art-rock songs that are more influential in the hip-hop community. She got so much done with a spookily repetitious rhythm and a single voice.

The Heart of a Dog album was the soundtrack to a film of the same name that had been commissioned by the French-German TV station Arte. She had worked with them before. The network had, since 2002, run a feature called Why Are You Creative?, in which the German director Hermann Vaske asked hundreds of artists, musicians, actors, and more about their creativity. It’s a great resource, and one that I’ll return to over the course of this book. I like Laurie’s segment, which was broadcast in 2002 but probably filmed five years or so earlier. It starts with the usual Vaske question: Why are you creative?

Laurie takes a beat. “As opposed to, like, lying on the beach and just swimming and things? It can be creative. I like to pretend that I’m being creative when I’m lying on the beach.

“Why? It makes me laugh. It makes me feel like I can change things. It means something different almost every day because I’m what you’d call a multimedia artist. Some days I’m working on music. Some days I’m working on animatronics or just fixing computers. That’s one of the big new jobs that I’ve gotten as an artist. In terms of what it actually means, I don’t really know. The most exciting art I see is things that redefine it, and you kind of go, ‘Is that art? I’m not sure.’ I like it when it’s just not so clear if it’s art or politics or something else. I probably trust laughter more than anything that goes through my mind. If I really am laughing, I am thinking there’s something here that is physical as well as mental.”

And then she laughs, proving the point.

The thing that lingered, at least for me, was the other part of her answer. She makes things because it makes her feel like she can change things. It’s a world where we grapple all the time with our insignificance, where things happen around us and to us. Being creative, in whatever form, is the proof that we can leave an imprint on our surroundings, that we can make a mark on time. Even her expansion of the definition of art into politics “or something else” stays faithful to this idea of creativity. When we make something, we make something different.

Laurie’s definition is one of the best and broadest that I’ve seen. Her answer sparked a series of thoughts in me, and one of the first was about the question of audience. It got me thinking about who I am talking to throughout this book. Who exactly do I mean when I say that I am addressing creatives? Is that the same as saying that I’m addressing artists? If so, what kind of artists are included? What kinds are excluded? If it’s not the same, what are the differences between creatives and artists? Is it a question of talent? Is it a question of motive? Is it a question of which rewards are delivered, and how quickly, and how consistently?

Let’s answer the question by starting with an indisputable. Some people have talent, no matter how you slice it. Take someone like Tariq Trotter, my partner in the Roots. Tariq is an artist, through and through. When we met, he was a fellow student at the Philadelphia High School for the Creative and Performing Arts (CAPA). He came in as a visual artist, with a huge amount of talent at drawing, and his talent expanded into writing and then rapping. Someone like Tariq is a source of intimidation. I don’t mean that he himself is intimidating. I mean that when people start down the road to their own creative satisfaction, people like Tariq distort the field. They generate unrealistic expectations. And even Tariq—an artist in every way—doesn’t fit the most exclusive definition of what some people would call an artist.

I want to reverse this whole movement of separating artists from each other, of saying that one man or woman is more or less of an artist than another one. For that matter, I want to broaden the definition to include anyone who is making something out of nothing by virtue of their own ideas. I include the dad who likes doing craft projects in the garage. I include the mom who sings on weekends and has started after twenty years to write songs again. I include armchair poets and sideways thinkers. I include the world, not because every creative project is equal in conception or in execution, but because every creative project matters to someone. Time will sort out the difference between whales whittled out of balsa wood and Moby-Dick and Wale. I’ll just say that while there is a difference, it may not be as great as some people believe.

The other reason for this definition is that it is a kind of activism. The people who already exist as artists know something about their own creativity. This isn’t to say that they don’t struggle with it… But I also want to reach people who are maybe not as sure about their own status as creative. Why? Because more creative work is one way to save the world. Is that a grand claim? I hope so. Studies have shown that creative people tend to be more sensitive to the feelings of others and to fluctuations in the social fabric around them. At the same time, they are often less equipped to deal with those things. The result can be withdrawal from the world. Defense mechanisms, depression. Creative production is not only a way to avoid those pitfalls, but a way to connect those people to the rest of the world. Creativity creates connectedness.

Again, I’m defining it more broadly than most books about creative work do. If you’re a teacher in an inner-city school who is working hard to get kids involved in an antiviolence program, and as part of that you’re designing an ad campaign that needs slogans and a song, you’re being every bit as creative as the guy who’s writing a new jingle for a restaurant chain, who in turn is being every bit as creative as the commercial soul singer who is writing a new love song. The arrows are aimed differently, but they’re coming from the same bow.

Don’t get lost low down on the ladder trying to figure out who is creative and who is not, or why one kind of creativity is superior to another one. Start climbing…

From Creative Quest by Ahmir “Questlove” Thompson. Shared courtesy of the author and Ecco, an imprint of HarperCollins Publishers.

Ahmir “Questlove” Thompson is a six-time Grammy-winning musician, drummer, record producer, DJ, Oscar-winning filmmaker, author, and entrepreneur—known for his boundless creativity and deep reverence for music’s power to inspire change. In Creative Quest, he offers an intimate and expansive exploration of the creative process—drawing from a lifetime of artistic experimentation and soulful introspection. Through his work as the drummer and co-founder of The Roots, music director for The Tonight Show, and creator of multiple acclaimed projects across film, literature, and television, Questlove invites us to reimagine creativity as both discipline and discovery.

So what about you? What sparks your imagination—or blocks it? We’d love to hear how creativity shows up in your life ✨

Awww, I love Questlove’s take on creativity—the lack of hierarchy, the importance of defining what something isn’t. Thanks for this!

This is post Memorial Day goodness! I love me some Questlove and I love Soul Boom! Beautiful combination