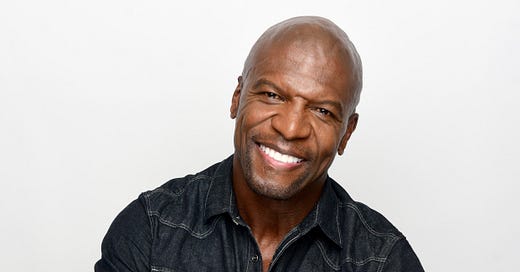

Exclusive Excerpt: Terry Crews on True Power

PLUS: Terry sits down with Rainn on the Soul Boom podcast

Greetings to all you Tough Cookies out there—

This week on the Soul Boom podcast: Terry Crews.

That’s right—the guy from Brooklyn Nine-Nine. The human protein shake from those Old Spice commercials. The man who can flex his pecs in perfect rhythm and make you laugh without saying a single word.

But this week on the Soul Boom podcast, Terry brings something more than laughs and muscles: vulnerability, wisdom, and the kind of radical honesty that makes you sit up a little straighter and maybe check your own reflection for signs of emotional avoidance.

Because behind the muscles and the memes—behind Brooklyn Nine-Nine, the Old Spice ads, Everybody Hates Chris, and his hosting of America’s Got Talent—is a story that’s raw, redemptive, and deeply soulful.

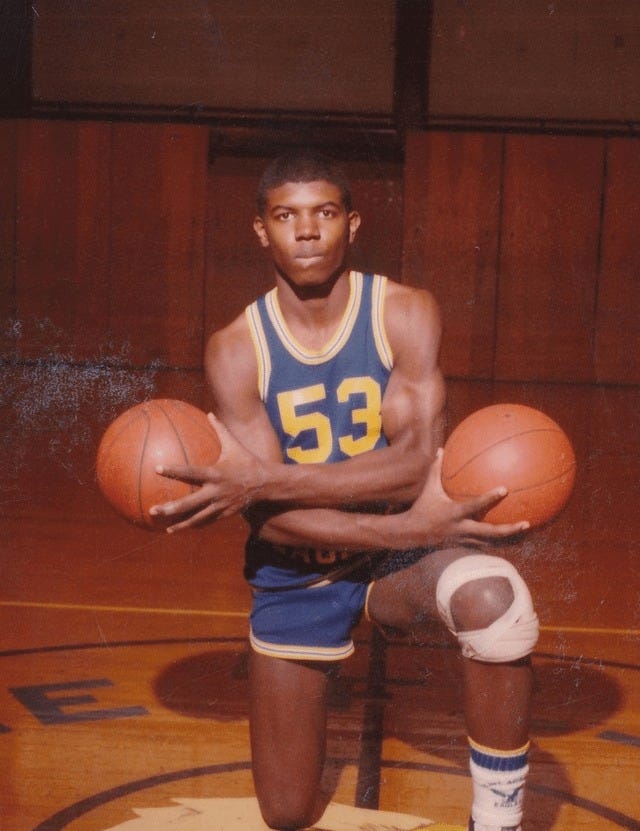

Terry grew up in Flint, Michigan, in a home ruled by fear and silence. His father was violent. His mother, devout and emotionally distant. He learned early that strength meant survival—and feelings were a liability. So he got big. He got loud. And he got funny. The world applauded the performance. Football. Battle Dome. The early roles. The memes. The flexing.

But none of it could heal the pain underneath.

In this episode, Terry opens up about the private life behind the public image—his struggle with pornography addiction, the confession that nearly blew up his marriage, and the years of painful inner work it took to become a man his family could trust again. He talks about masculinity, resilience, and the quiet power of choosing love over control.

And while this episode is a beautiful entry point—his memoir Tough goes even deeper.

The excerpt below is one of the most gut-wrenching and redemptive chapters in the book. Here, Terry recounts the moment he realized the same rage he once condemned in his father had taken root in himself. It’s a story of generational trauma, shame, and the long, humbling road to healing. But it’s also about transformation—about coming to understand what true “toughness” is.

As Terry writes:

“The purpose of being strong is not to dominate, but to support.

The purpose of having power is not to rule, but to serve.”

With tough love and soft hearts,

The Soul Boom Team

Excerpt from Tough by Terry Crews

A Recovering Chauvinist

One afternoon, I picked Naomi and her friends up from the mall, and they got in the car all weirded out because some skeezy dude had been leering at them and catcalling them.

These girls were fifteen years old. I asked the girls where the guy was, and Naomi pointed, and said, “Over there!”

To my surprise, the guy was sitting on a bench at the bus stop. I stomped on the gas and pulled the car right where the bus was supposed to go. I jumped out and ran around the hood, and stood over him as he looked up at me.

“Yo, man!” I hollered, pointing at Naomi and her friends as they nervously watched from the back seat. “Didn’t this girl tell you she was fifteen?”

“What are you talkin’ about?!” he said, acting all rude.

“Didn’t she tell you that she was fifteen?”

I didn’t even wait for him to respond.

POW! I straight up cold-cocked this dude.

He went down and hit the ground and I kept whaling on him. I looked like a pimp turning out a trick. Mind you, there were other people waiting at the stop, too. But as soon as I hit him, they split. Traffic was slowing down, and Naomi was sitting in the car, horrified in front of her friends to see her father doing this. I was so hell-bent on being “the man” protecting my family that I couldn’t even see the ways in which my toxic behavior was damaging to the very people I wanted to protect.

Finally, I smacked the guy one last time and got up and said, “If you see me before I see you, you’d better run, because I’m gonna kill you.”

What scares me today looking back is knowing that I actually meant it, that deep down, on some level, I was fully capable of it. I spent the next week apologizing to my wife and my daughter and waiting for the cops to show up, certain that someone had taken my license plate number down. But the knock never came. If that week didn’t end up with me in handcuffs, it should have at least ended up with me in a therapist’s office.

It didn’t.

Things only deteriorated from there, and it wasn’t just me. Naomi and Rebecca butted heads, too. There was one time Naomi talked back, and Rebecca snatched her by the collar and demanded she respect her parents. Naomi complained to her friends, and their parents called social services. A representative came to the house and interviewed all the kids. I was terrified that I was actually going to lose my kids that day. Luckily, we didn’t. But there was no fixing things with Naomi. When she turned sixteen, she took the California High School proficiency exam, left high school early, moved out of the house, and moved in with a friend.

I can still remember being Naomi’s age, living with my father’s rage and my mother’s obsessive need for control, not being allowed to date or do anything I wanted, lying awake at night with a burning desire to be anywhere but at home with my family in Flint. I swore I would never be like either of them. Now, two decades later, my rage and my need for control had produced a child who hated and resented me as much as I ever hated and resented Big Terry and Trish, which meant somewhere I had gone horribly, horribly wrong. Two years after that, the drunk guy pushed my pregnant wife on Colorado Boulevard, and I exploded and nearly wound up in jail.

Something needed to change, but looking yourself in the mirror and facing your demons is the hardest thing you will ever do in your life. You will duck it and avoid it—and make excuses for ducking it and avoiding it—for a long, long time. I avoided it by throwing myself into work. I threw myself into project after project, filming movies and TV shows back to back to back. I was running away from myself as fast as I could, never stopping to look down or pause for a moment’s self-reflection. I did that for years, even though I knew something was deeply wrong with me, even though I’d lost my daughter and nearly put myself in jail, even though my marriage and my family were barely holding on.

Then, in February of 2010, I finally broke down and confessed my infidelity and my pornography addiction to Rebecca. We called it D-Day. It blew our marriage to smithereens, and we were left standing in the rubble, figuring out how to rebuild it—if we even wanted to rebuild it. It was a wasteland. There were days when we wouldn’t speak, days when it was nothing but tears, days when everything would seem normal and then it would all fall apart. I’ll be honest, every instinct in me was to run. I was afraid to sit in the mess I’d made and deal with it. There were times when I thought, “I should drive away and never come back. Everyone’s hurting, and I’m the one who hurt them, so I’ll just leave. I’ll leave my kids. That would be the best thing for all of us. I’ll wipe the slate clean and start over.”

But as Rebecca and I clawed our way back, I started going to therapy and started to have small breakthroughs, epiphanies. I was so profoundly embarrassed to learn, at fortysomething years old, how ignorant I had been about the workings of my own mind—that I was so ignorant I’d been ignorant of my own ignorance. I never wanted to be in that position again, of not knowing what I didn’t know, and I vowed I never would be. I developed a hunger to learn everything I could about human nature. I read everything I could put my hands on. I read books about addiction, psychology, how the brain works, anything to try to figure out what was happening with me, and how I had come to end up in the circumstances I had.

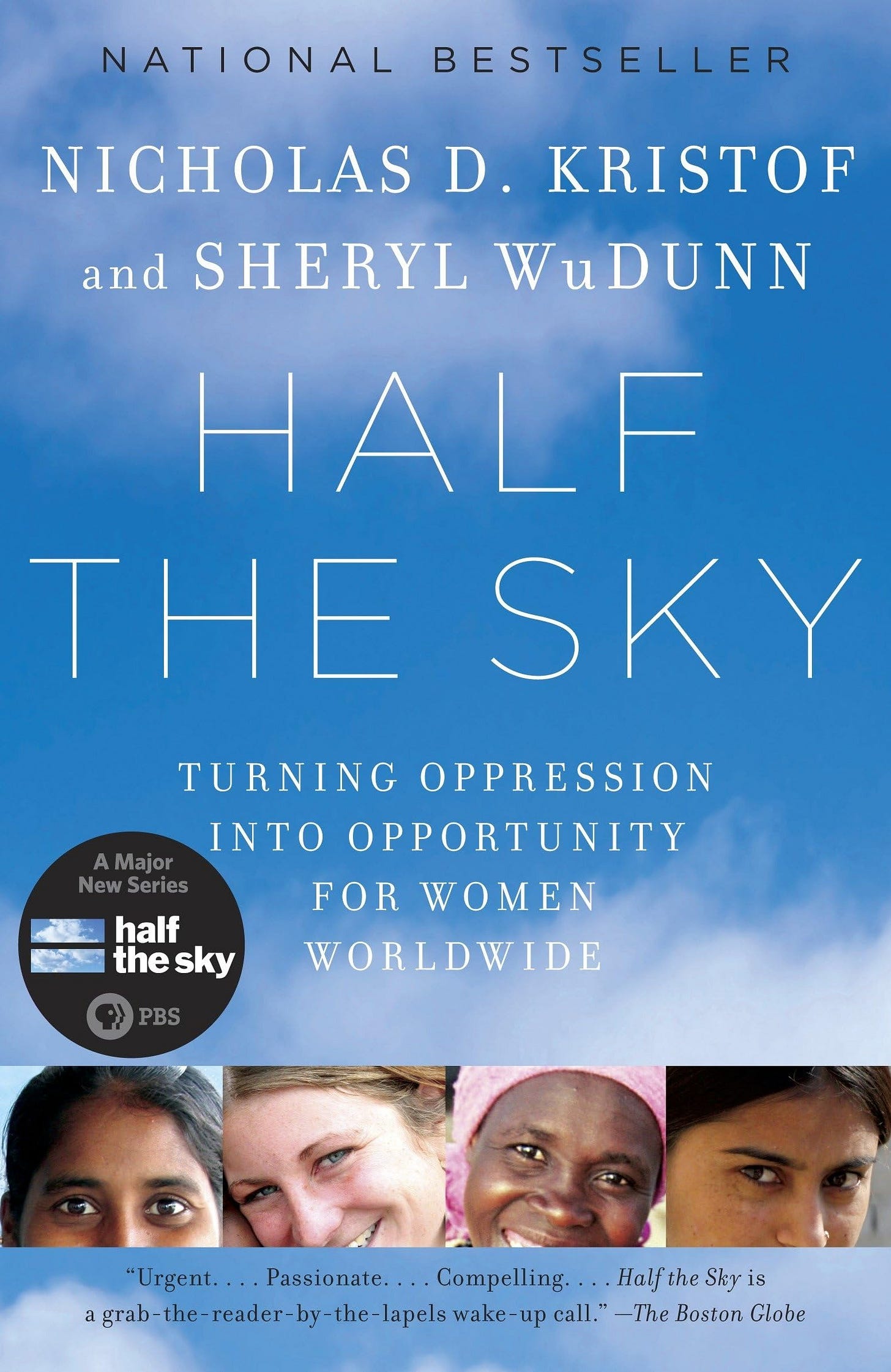

It was around that time that I read a book called Half the Sky, by Nicholas Kristof and Sheryl WuDunn. It’s a book that documents the plight of women around the globe, women held in sex slavery, women subjected to rape in war—all the ways in which women are still, to this day, treated as property, as objects, by men. It hit me hard, like a blow to the chest, when I realized that that was me. For twenty years I had treated my wife as my property. Our situation wasn’t nearly as brutal as those described in most of the book, of course. But it was the American version of the same story. I’d worked hard, become successful, and put my wife in a gilded cage. It had always been my mentality that I was the more important person in the relationship than her, simply because I was the man.

To this day Rebecca calls me a “recovering chauvinist.” And it’s true. I was a grade A, bona fide, card-carrying chauvinist. Because everything in my life, all the lessons I’d learned from my role models growing up, had told me that that was the way to be. Men were always the heroes of the story, the protagonists. Women were mere objects, trophies to be won and then controlled and, if they could not be controlled, discarded. I’d felt the same way about my daughters. Like Rebecca, they were all supporting players in the Terry Crews story, but it was always my story.

The deeper discovery, for me, was that my treating women and others as objects wasn’t merely damaging to them. It was the thing that was destroying me. From the earliest days of my childhood, paralyzed with fear in my bed as Big Terry bounced Trish off the walls, I’d felt powerless. I couldn’t change anything. I couldn’t fix anything. I had no control, over anything, and control was all I wanted. If I could just make my mother happy, if I could just get my father to be happy, there would be peace.

I was so desperate for that peace, I became obsessed with trying to control things I had no ability to control. But there’s so much in life that’s beyond your control, especially other people, particularly your wife and kids. I’d become fixated on finding the peace and happiness that I didn’t have, and if I could just get my wife to do what I wanted, if I could just get my kids to behave the way I wanted, then life would be what it was supposed to be. But you can’t love people and control them at the same time, because control is not love. It’s manipulation. It’s abuse.

The same can be true for women; any woman can be possessed by that same need to control others. What’s different for men is that, from the day we are born, we’re told that we ought to be able to control women, that we’re supposed to control women—and if for some reason we can’t control women, then somehow we’ve failed as men.

It’s all a lie, but I had lived my life beholden to that lie, and that lie was also the thing at the root of my anger. When I look back at my life, every time I snapped and I lost it, it was always the result of something not going the way I had wanted it to, or someone not doing what I had wanted them to. When the people you think you control don’t behave in the way you want, you get frustrated. When you get frustrated, you get angry. And anger, when left to fester, curdles into rage.

My father turned his rage inward with the bottle and against my mother with his fists. I thank God every day that the physical violence I inflicted in this world was never against the people I love. I poured it out on the football field and took it out on skeezy dudes hitting on my daughter at the mall—and, yes, on the dog. But words can hit as hard as fists, and I unleashed them on my family more times than I can count, and I still ask their forgiveness for that nearly every single day.

Once I had this revelation, I went to Rebecca and said, “I want to start over. I want to change.” She looked at me skeptically. She started recounting all the ways I’d manipulated and controlled her and the kids, and I said, “I know.” I literally got on my knees and apologized. “I’m sorry. I had it all wrong.”

In the age of social media, a lot of jargon gets used and misused and overused to the point of cliché. In feminist circles, phrases like “patriarchy” and “male privilege” and “toxic masculinity” have gotten played out, almost to where you roll your eyes every time you hear them. But whatever jargon you use, the issue that’s really at stake is the abuse of power.

Not all marriages are built around a male breadwinner, but our marriage was, in part because the NFL and Hollywood took us where they took us, but mostly because I’d never even allowed us to entertain any other option. In any marriage with a sole breadwinner, the breadwinner has a great deal of power. Rebecca had given me that power, and I had abused it.

Men wield power in this world because of our size and our strength, and because society gives it to us whether we deserve it or not. For almost all of my adult life I thought the purpose of having that power was to win, to dominate, to control. I felt so helpless as a kid. I had to do what everyone else said. I had to endure my father’s abuse. It was always “sit down and shut up.” So I made myself into the biggest, toughest man I could. But it was all a front, a fake toughness.

The purpose of being tough is not to attack, but to protect. The purpose of being strong is not to dominate, but to support. The purpose of having power is not to rule, but to serve.

What I’ve learned is that to be a true man is to be the ultimate servant. With any talent or advantage that life has given you, whether by birth or by circumstance, your duty is to put that advantage in the service of others.

The best men I’ve ever known in my life, the father figures who’ve rescued me from having no good father of my own, have all been driven by a generosity of spirit—and not just generosity, but a creative generosity, finding new ways to share and create opportunities for the people around them, because doing so makes life better for everyone. My middle school football coach, who went out on a limb with my parents to get me on the team. My high school art teacher, who got me the scholarship that allowed me to go to college. Mentors in Hollywood like Sylvester Stallone, who believed in me and stood up for me when I didn’t have the stature to stand up for myself.

In fact, I can honestly say that the toughest, most masculine thing I’ve ever done was not stomping a man who bumped the arm of my pregnant wife. The toughest, most masculine thing I’ve ever done is to come forward as a survivor of sexual assault, because it was something I did to put my strength and my power in the service of others, to try to protect the voices of those who were scared to come forward themselves.

I still have an ego—a huge, huge ego. I spent my whole life trying to satisfy that ego by getting more and more for myself: more money, more power, more control. But the ego was never satisfied, because those things can never satisfy you. But once I humbled myself and put myself in the service of others, guess what. The ego was finally sated. I was nourished. Because by using my strength on behalf of others, I was finally serving my purpose as a man.

I still have feelings of rage, too. They haven’t entirely gone away. But now that I know what they are, I know how to deal with them. Anytime I’m feeling those stirrings of rage, it’s coming from some feeling of insecurity, some loss of control. Somebody got a part in a movie I wanted, and now I’m worried my career is over. I had some plan or idea of how the day was supposed to go, and something’s thrown it out of order. I feel that rage coming on and I tell myself, “Yo... relax. You’re good right where you’re at.” Because I am good right where I’m at. Life’s a game of musical chairs; sometimes you don’t get a chair. You can either get mad that you don’t have a chair, or choose to be happy doing something else.

I choose to be happy.

We were on a family vacation in Hawaii not long after I started to turn things around with Rebecca. My son spilled his drink at the table and it went everywhere, making a huge mess, and everyone froze. They all looked at me and held their breath, waiting for me to explode. I didn’t. I grabbed a napkin and started sopping it up and I said, “Hey, man. That’s okay. Everyone makes mistakes.”

Rebecca and the girls could not stop looking at me, and eventually I said, “What?”

“Holy shit,” Rebecca said, “you are a different person.”

“What do you mean?”

“Three years ago you would have gone off if one of us had spilled that drink.”

I thought back to the person I used to be, and I realized she was right. I would have lost it. I would have yelled, “Man, come on! Do you know how much we paid for this dinner?! Watch what you’re doing!” Because I was always being driven by my own insecurities, which had nothing to do with my son having an accident.

“Terry,” Rebecca said, after dinner was over and we were getting up to leave, “you’re different. I can honestly say you’ve changed. I have never seen you that patient and that caring.” Then she hugged me and said, “Now I know I’ve got a new man.”

Excerpted with permission from Tough: My Journey to True Power by Terry Crews. Published by Portfolio, an imprint of Penguin Random House. Copyright © 2022 by Terry Crews. All rights reserved.

Terry Crews is an actor, artist, activist, and former NFL linebacker, best known for his roles in Brooklyn Nine-Nine, Everybody Hates Chris, and White Chicks, as well as for his iconic Old Spice commercials and work as host of America’s Got Talent. Beyond his comedy and action-hero status, Crews has become a leading voice for vulnerability, emotional healing, and redefining masculinity. A lifelong artist, children’s book illustrator, furniture designer, and human rights advocate, he was named one of TIME Magazine’s 2017 Persons of the Year for speaking out during the #MeToo movement. He is also the author of multiple books, including Manhood: How to Be a Better Man-or Just Live with One and the graphic novel, Terry’s Crew. In his recent memoir, Tough: My Journey to True Power, Crews chronicles his path from a childhood marked by fear and control in Flint, Michigan, through professional sports and Hollywood, to a spiritual and emotional transformation rooted in love, humility, and service.

So what do you think Soul Boomlets? What’s your definition of toughness?

I have a lot of respect for Terry Crew he is seeing the changes he has worked hard to change. Not an easy thing to do.

Toughness is the most delicate of surgical procedures: with humility as the scalpel, I have to remove my ego without disturbing my self respect. It has taken years, and the procedure is still not complete. Removing the ego is the key to happiness and to everything else. Here's what I mean by tough: even as I am writing this, I am thinking, "Does this make me sound smart? How many likes will I get?" I have to keep telling myself that it isn't all about ME.